The operation done by ECB hasn't worked so far. Their LTRO 1, and LTRO2 had minimum effect on Spanish and Italian 10 year bond yield. ECB carried the same SMP program today which it launched in May 2010. During that time Italian 10 year yield was at 4% and now at 5.70%. Same way in May 2010, Spanish 10 year yield was at 4.64 and now at 6.65%.

|

| ECB LTRO 1 and 2 effect on Spanish 10 year yield. |

|

| ECB LTRO 1 and 2 effect on Italian 10 year yield. |

|

| Performance of ECB SMP program on Dow Jones. |

SMP 1 was a failure. SMP 2 won't make much difference.

While this programme of the ECB did not return sovereign debt markets to their path prior to the financial crisis, it would be unfair to state that it completely failed. Indeed there is evidence to consider that to some extent the SMP might have worked, when it was used.

What are sovereign debt bonds?

Sovereign debt bonds are financial contracts which are auctioned by the governments of sovereign states, as a means of financing their budget deficits. Through these contracts the governments of our countries acquire debt from financial markets. As with everything else they have a jargon of their own:

- Principal is the total amount being borrowed

- Coupon is “the interest paid on a bond. They are called coupons because formerly they were represented by physical coupons on the bond certificate that had to be clipped and returned to the issuer to receive the interest payment. With the advent of computers, this has become much less common.”

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is a specific rate of return “r”, say “IRR*”, at which the Net Present Value is equal to zero. It is not always possible to calculate IRR analytically.

- Net Present Value (NPV) = Sum[(Coupons)/(1+ r)]

- Yield refers to a specific formula used to determine the fair value of the bond. It normally refers to one of the following:

- Nominal Yield = (Coupon)/(Principal)

- Current Yield = (Coupon)/(Bonds Spot Market Price)

- Yield to Maturity = Total IRR

- Yield to Call = IRR until the bond is sold.

Government bonds are generally quoted in terms of their current yields. These quotes can be found in Bloomberg and interactive graphical data is available through it. Nominal yields are relevant at the time of a bond auction.

Mechanics of the SMP: How does it work?

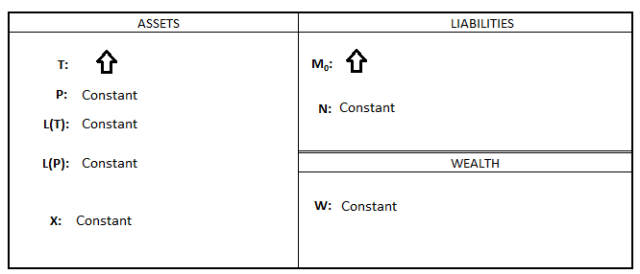

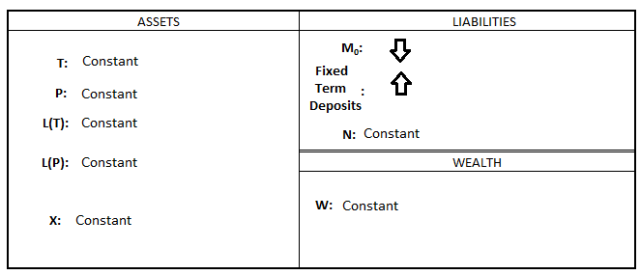

In that May 14, 2010, the ECB specified the details of the programme. The short version is that through the SMP, the ECB purchases government bonds, in secondary markets, in order to provide liquidity to alleviate pressures from sovereign debt risk on the balance sheet of MFIs. To limit the inflationary effects of those purchases, the ECB then sterilises these open market operations by auctioning fixed term deposits at the ECB, in order to stop the banking sector from increasing its loans to the overall public and increase inflation. Therefore, the SMP is effectively the official name of what would otherwise be known as sterilised debt monetisation. On the ECB’s balance sheet, this occurs as a combination of 2 steps:

Step 1: In a Structural Operations, the ECB outright purchases government bonds of some affected country.

Step 2: A Fine-tuning, liquidity absorbing operation, aimed at limiting the potential inflationary effects of the operation carried out in the first step.

Although the second step is done to alleviate inflationary pressures, the truth is that all that the sterilisation step produces is postponed inflation, probably at a premium proportional to term and risk free rate (clearly counter party risk do not affect the ECB

Fixed Term Deposits

Due to inflationary concerns, the ECB, ever-so-worried about price stability, attempts to sterilise the effect of its Securities and Market Programme (SMP), through which it purchases sovereign debt, by auctioning Fixed Term Deposits. According to the ECB, these are “monetary policy instrument[s] available to the Eurosystem for fine-tuning purposes. The Eurosystem offers remuneration on counterparties’ fixed-term deposits on accounts with the national central banks in order to absorb liquidity from the market”. This means that “when a term deposit is purchased, the lender (the customer) understands that the money can only be withdrawn after the term has ended or by giving a predetermined number of days’ notice”. By pursuing these operations, the ECB ensures that the extra liquidity of the SMP is held in reserves rather than going into operations and loans so that it does not multiply through the economy, thus slowing inflationary pressures. Of course this isn’t automatic. The process is still voluntary, so it can fall short of the target, in which case the sterilisation will not be sufficient and as such could possibly lead to higher inflation. Moreover, this is only a temporary solution, given that in these deposits will mature and the ECB will have to pay them back to depositors, with interest. Fixed Term Deposits are postponed inflation. Of course, under the present (2011-2012) circumstances, where economic stability is still a target rather than a reality, with (probably) spare capacity and scarce liquidity, this is not necessarily an issue, and thus one can be excused for thinking the ECB is erring on the side of caution.

Period of Operation

The Governing Council of the ECB decided to intervene in the secondary markets for “public and private debt securities markets” on May 10, 2010. The details of the intervention were later elaborated on in an ECB decision issued after the next ECB Governing Council meeting on May 14, 2010. The figure below illustrates the intervention of the ECB in government debt markets since the inception of the SMP until the last week of February 2012.

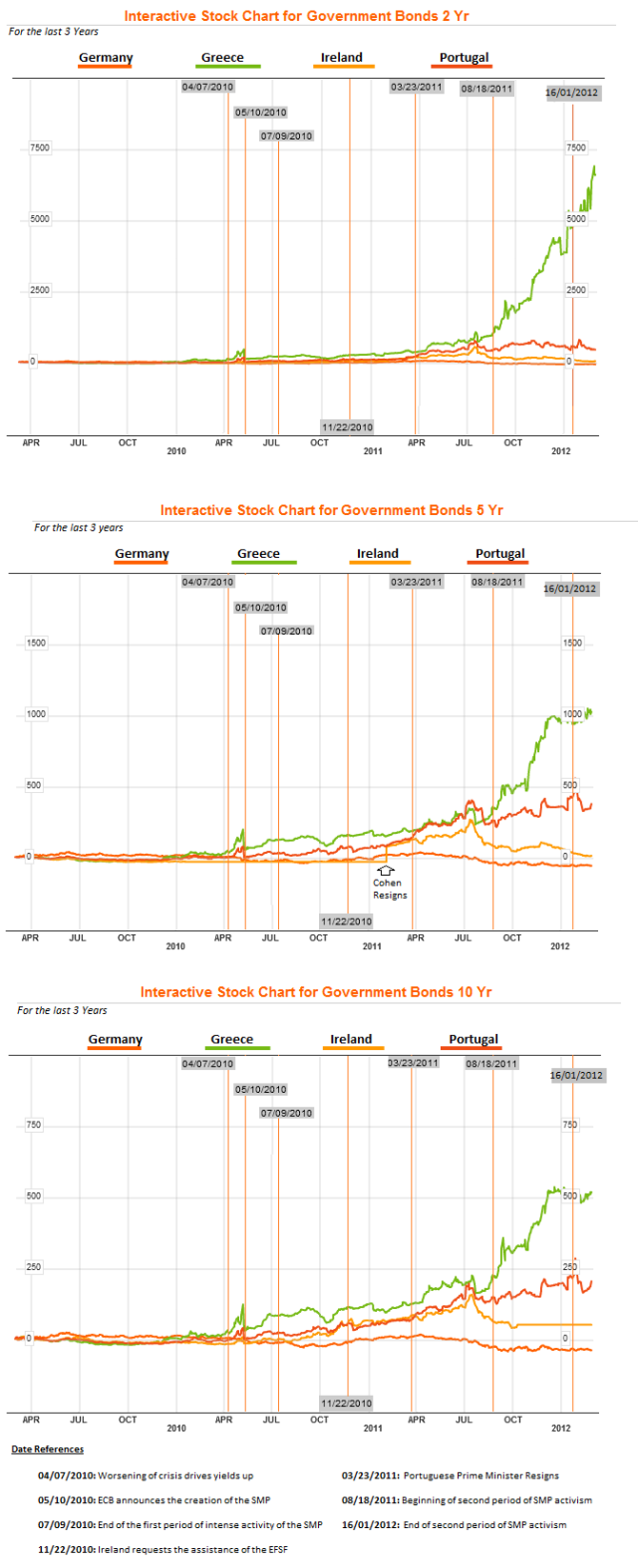

This figure shows that the SMP was mainly active during 2 periods. The first, immediately after its inception, lasted until the week of July 9 2010. The second period occurred between the week of August 15 2011 and the week starting on January 16 2012. This latter intervention was particularly active in its first weeks of operation, until October 2011, with fluctuations on its activity from there onwards.

Causes of the creation of the SMP

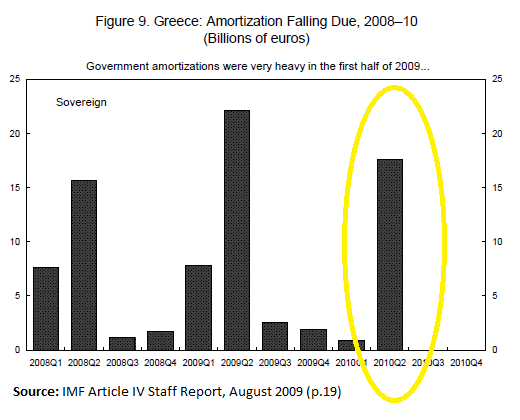

The creation of the SMP is closely related to the Greek debt crisis, which triggered the sovereign debt crisis in the rest of the continent. The rise of Greek bond yields started in September 2008 due to the liquidity shock created by the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers. While it pushed yields upwards in all European capitals, this event had the added effect of decoupling Greek yields from the European neighbours it had been following for a decade. This decoupling accelerated from November 2009 as elections and a new government began to highlight discrepancies in the data collected domestically and the one provided to EU institutions. These fears gained momentum in December 2009 and January 2010 onwards, as the Council judged that Greece has not responded adequately to its March warning and the European Commission publishes a report recognising statistical fraud had occurred in Greece. Finally, the situation reached a critical point in April 2010, as the Greek state, unable to access credit in financial markets, seemed increasingly unable to find the resources necessary to pay an extensive amount of debt maturing in the second quarter of 2010 (The image below is taken from the IMF article IV staff report, published on August 2009).

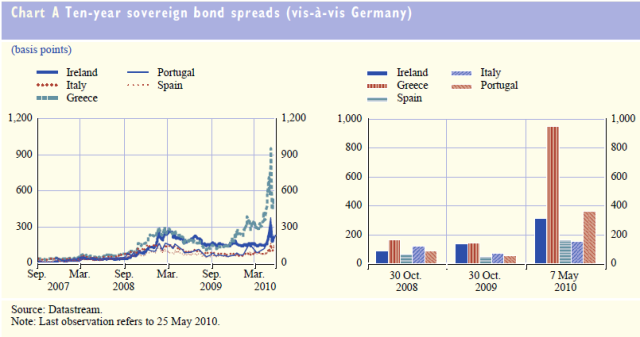

This forced it invite a joint EC/IMF/ECB mission to Athens on April 21, 2010, with which itagreed an adjustment on May 2, 2010. However, it had become apparent that the problem was no longer confined to Greece. Indeed, as yields started to rise in Ireland and Portugal, contagion became the overwhelming fear. In an attempt to improve expectations and stabilise markets, European leaders agreed to the creation of the EFSF, on May 9, 2010.This fiscal commitment made intervention a justifiable policy path for the ECB which announced the creation of the SMP a day later.

In the May 10, 2010 press release, the ECB made the following statement

“The objective of this programme is to address the malfunctioning of securities markets and restore an appropriate monetary policy transmission mechanism.”

The ECB made specific mention to these and other issues in its Monthly Bulletins of Mayand June 2010.

Consequences of the SMP

Not withstanding these facts, an independent analysis, although likely to be conducted on this website in the near future, is beyond the scope of this particular post. So for now, I will limit myself to the analysis of some time series, aided by the knowledge of the timing of some events.

Assuming that the ECB’s goal in introducing the SMP was indeed to “restore an appropriate [and functioning] monetary policy transmission mechanism” to financial markets, by stabilising sovereign bonds, then it would appear that to date, the SMP has failed. Clearly as the figures below show, there is still turbulence in the markets. However, this very narrow interpretation of the consequences of the SMP would miss the details.

SMP: 1st Period of Activism

Considering the periods of intervention uncovered before, it seems that the first period of SMP activism by the ECB was relatively successful in bringing sovereign debt yields down. However its discontinuation led to a progressive rise in the yields of Greece, Ireland and Portugal. However, as the figure below shows, the second period of ECB activism did not have the same effect on the yields of the three bailed out countries.

SMP: 2nd Period of Activism

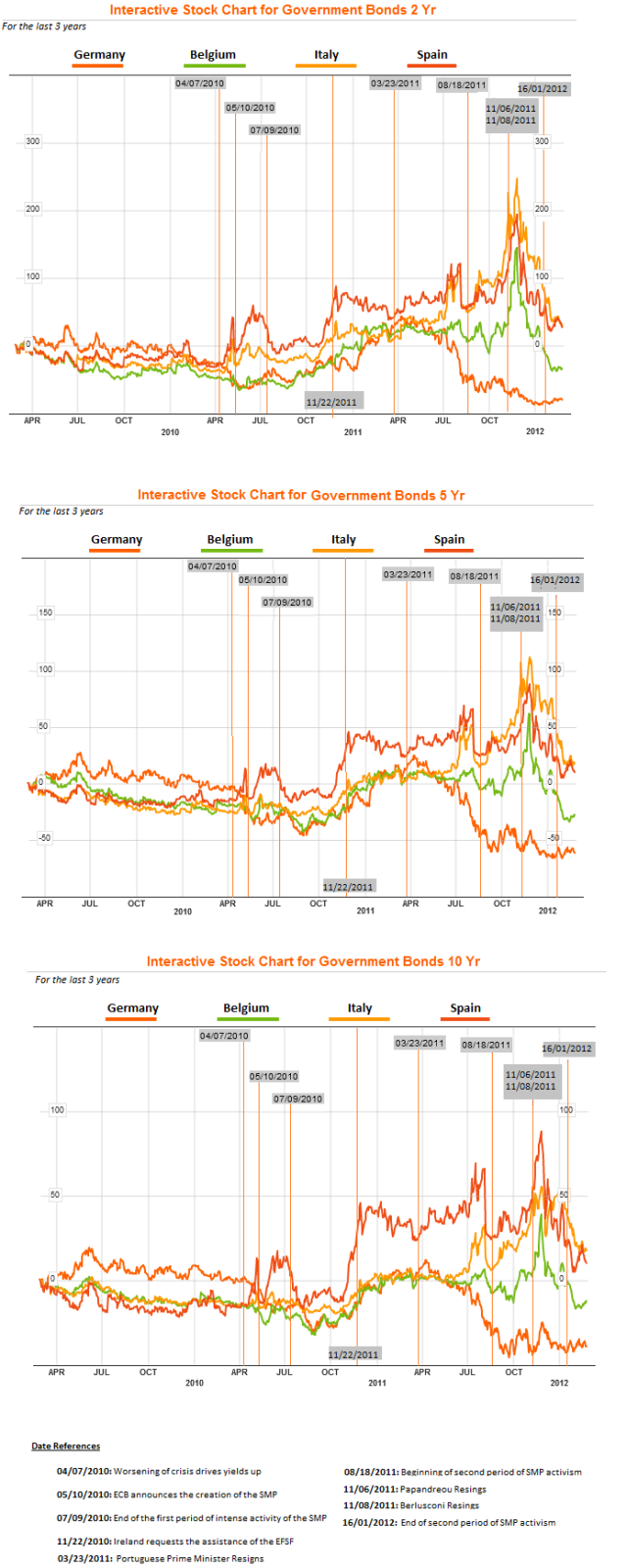

Interestingly, the effect of the SMP does not seem to be constrained to the countries above. Indeed, while the above might present a reactive behaviour on the part of the ECB, it is possible to describe its behaviour as of a much more preventive nature in Italy and Spain. As the figure below shows, and as was commented at the time, that the second period of SMP activism seems to have been targeted at managing Spain and Italy.

Between August and the beginning of November, the debates about PSI and the second Greek adjustment programme pushed contagion to Italy and its unresponsive political system. Moreover, the uncertain political climate in Spain, on the eve of the November 20 elections, inspired the volatility that is evidenced in the figures below. However, as bureaucratic governments took over in Italy and Greece as well as a more fiscally conservative government in Spain, the ECB’s intervention seems to have been more successful.

Although these descriptions might shed some light on the events that took place between 2010 and the Q1-2012, they are presented under no illusion of providing a causal explanation. It is impossible to tell whether the fall in Italian and Spanish yields was caused by political developments or by the ECB’s intervention without more sophisticated methods.

Conclusion The SMP is a tool used for Debt Monetisation in the Euro-Zone. It is carried out in 2 steps and is meant to stabilise a specific financial sector responsible for monetary policy transmission: the sovereign debt markets. While this programme of the ECB did not return sovereign debt markets to their path prior to the financial crisis, it would be unfair to state that it completely failed. Indeed there is evidence to consider that to some extent the SMP might have worked, when it was used.

However, the fact that purchases were reined in to a considerable extent probably points to the fact that its impact on this specific financial segment was not as strong as the CBPP was or as similar programmes in the UK, USA and Japan. The conclusion must inevitably be that the ECB’s passivity and the fiscal austerity that accompanied it were the price of avoiding political moral hazard.